Photo by Michael Brace - Creative Commons - https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/legalcode

Handling the Crossover Point between Requirements and Design Work

Summary

Backlog refinement may involve crossing over from the “what I want” mindset into the “how to do it” mindset. This is often necessary to boil out the Backlog contents and discover what needs to be done. But it is risky. It can lock a system into a design too early, without including all the right people. We should be aware when we are moving into “design think”, understand why we are doing it, and stopping ourselves before we cross too far across the line.

Requirements, Features, and Stories

Understanding how to navigate the dividing line between requirements (what is needed) and design (how to do it) is not an agile-specific issue. It was addressed in ISPI’s “Requirements Engineering” courses in the 1990’s, and in industry literature long before then. Now, we tend to refer to requirements as “Features” and “Stories,” but the question of how deeply we should define a story is the same one as when we call them “requirements.”

(The concept of documented requirements ranges from thick specification documents to notecards with a couple of statements on each one. Some agilists argue that self-expressive code and internal documentation makes all documented requirements/features/stories useless holdovers from antiquity. I may tackle that in another article.)

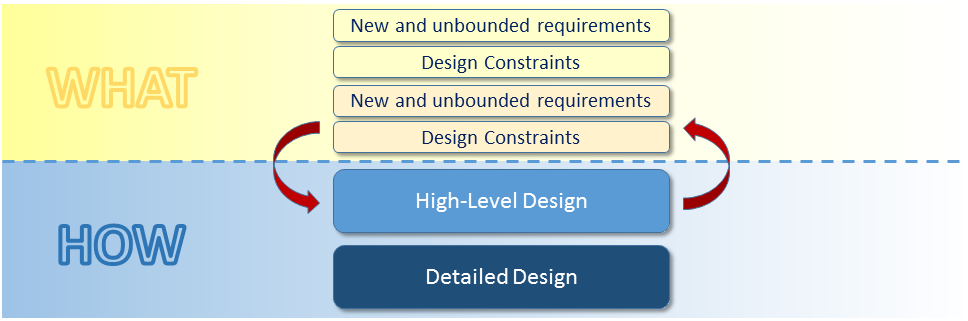

In conventional systems development, we realized that having one-directional progression between requirement and design activities is not realistic. Agile methods are more explicit about this being a bad idea. While requirements/stories guide design, it’s not a one-way flow of information. Design work also results in discovery that helps us refine our Features and Stories.

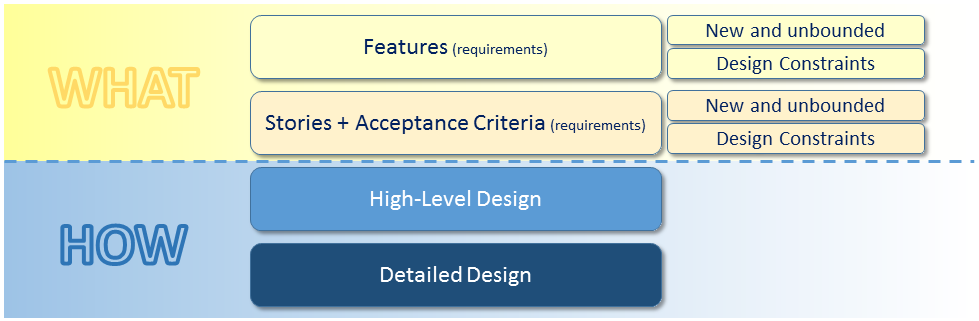

Defining Features and Stories means identifying a combination of things we want the system to do, and things that constrain how we can do it. Sometimes these constraints are iron-clad, defined by law, policy, or financial constraints that can’t be budged. Sometimes they evolve from knowledge of the technical environment and limits on how solutions can be implemented.

Systems thinking often involves stepping across the “what versus how” line to discover and evaluate perceived constraints. This risks leaping to design, so be aware when the conceptual divide has been crossed, learn what needs to be learned (via a prototype, proof-of-concept, or other activity) and then step back to the “What” mindset to define the learning within your User Stories. In a strong, dynamic team this line will be crossed and re-crossed on a frequent cadence.

The “three amigos[1]” backlog refinement concept means that those with extensive “what” knowledge (Product Owners) frequently meet with those having extensive “how to do it” knowledge (developers and SMEs) and “how to prove it” knowledge (test designers.) This collection of skills allows User Story decomposition to navigate the what/how dividing line without straying across too far and for too long.

The second type of constraints mentioned above are those based on existing system knowledge. They can be dangerous. Often such constraints come from a precursory exploration of the problem space, followed by leaping to “solutioning.” Such leaps give a comforting feeling that the way forward is known, but limit our willingness to consider options. A clear danger sign is when a Product Backlog is filled with stories that read like design constraints. It could mean one of several situations have happened:

1. Sponsors and Product Owners have been doing “armchair designer” work, possibly without involvement of the development team. The fine line between requirements and design has been crossed without looking back. (We’ll discuss this a bit more, farther on.)

2. Big Design Up Front (BDUF) has taken over, which risks emotional and financial attachment to decisions that probably are subject to change. This can happen when Product Owners abdicate their role of defining business need and value, leaving it to the developers to "wing it."

3. As more is learned, the make-versus-buy analysis (which shouldn't be a one-time thing) is shifting strongly to using existing components. This may not be entirely bad — sometimes "buy" or assembling existing components is the right way to go — but keep using your critical thinking.

4. Preconceived notions are being pushed for political or other reasons. Addressing that topic is figuratively opening a whole 'nuther can of snails; we won't go there in this article.

Acknowledge Constraints, Refine Through Recursion

BDUF risks high investment in work that is subject to change. We don’t want a backlog full of design constraints. But opposing too much design up front often causes a fanatical opposition to any design analysis up front. Such agile purism stops using design discussion in its tracks. Do avoid having a backlog fill up with design constraints and presupposed design decisions, but don’t stamp out all design discussions during story elaboration. Build the recursive relationship between “what” thinking and “how” thinking.

In Agile Software development, the recursive aspects of needs definition (which was used in the Modified Waterfall, spiral, and other pre-manifesto approaches) is made a constant behavior. Evaluation activities happen frequently, with participation required by key players. This shortens timelines by lessening the “information float” between figuring out what I want, and whether I am limited in how I can get it. Done well, it limits time lost on defining Features and Stories, and may limit the number of times they have to be revisited before and during their development.

A Contract Scenario

Software work sometimes takes place in contract situations, wherein the sponsoring organization doesn’t have software engineers as direct employees. This sort of situation was the cradle in which the Waterfall software life cycle was born. (By the way, the first descriptions of Waterfall by Winston Royce were instructions on how to make the best of it in DoD contract situations; they were not promoting it.)

In contract situations, the project sponsors often will attempt to make good use of time by specifying the system as early as possible. This can be false economy. Significant backlog refinement before the systems development team is present poses risk:

“Specification fatigue”

Design lock-in

Impatience with developers (“Get out of your analysis paralysis and just do it the way we said!”)

The sponsorship/product ownership team bing highly technical may can mitigate some risks but create additional ones.

There is a tendency to specify things based on deep knowledge of existing systems and constraints. Some system aspects may appear to be “immovable objects,” leading to stories and prioritization that appear obvious. This misses out on perspectives and opportunities that developers may bring. This relates to the “throwing requirements over the wall” behavior (described by Rob England as the Dead Cat Syndrome.[2])The Product Owners and Subject Matter Experts should be flexible in their thinking, and cautious about creating design constraints.

The PO team brings experience with the operational environment in which the new system will run. They may be familiar with its volatility, constraints, and peculiarities. This risks premature assumptions about the application architecture and eliminating new technology.

This provides understanding of how to ask for data or external processing that is needed. The risk is overly specifying where data will be and how to access it too far in advance; those tend to change in complex environments. This risk requires timing data discussions in sync with other development and maintenance work.

Mitigating Activities

· If the Development team is not yet onboard, slow the pace of story definition. This will address the temptation to create exhaustive backlogs and emotional commitment to what is in them.

Discuss existing systems and how they function in order to inform the process and stories. View all resulting stories with caution; use systems specifics as a guide but realize they are subject to change.

Treat stories/requirements that deal with information handoffs and interfaces as having higher risk. Touch on these early but revisit them often.

Identify general design constraints early, such as modifiability, modularity, and interoperability.

Always be ready to change or eliminate design decisions. At some point you do need to commit, but do that at the latest responsible moment.